publications test

peer-reviewed publications in reversed chronological order. generated by jekyll-scholar.

You can view a full list of my research activities here

2025

Journal Articles

-

The role of epistemic reasoning in mutual exclusivity inferencesKhuyen N Le and David Barner2025under review, preprint

The role of epistemic reasoning in mutual exclusivity inferencesKhuyen N Le and David Barner2025under review, preprintWhen encountering a novel word, adults and children as young as 12 months old often reason that it refers to a novel object rather than one with an existing name – making a ‘mutual exclusivity inference.’ We explored the mechanism of this inference, aiming to differentiate between three hypotheses: whether mutual exclusivity arises due to reasoning about a specific speaker’s knowledge, projection of one’s own egocentric knowledge, or reasoning generally about the conventionality of labels. Adults and 3.5-5-year-old children in our experiment heard a label being either taught or invented on the spot. They were then asked to decide what another label, produced by a speaker who was absent during the first label’s introduction, referred to. Our results revealed that adults and older children made more mutual exclusivity inferences when the first label was taught compared to when it was invented. Additionally, they were more likely to exclude the previously-labeled object in the referential choice if they judged that the speaker also knew the label, regardless of how the label was introduced. Both adults and older children also showed sensitivity to the speaker’s explicit statements of knowledge, excluding an object that the speaker explicitly stated that he did not know the name of from their referential choice. These results suggested that adults and older children reasoned about a specific speaker’s knowledge of labels in order to make mutual exclusivity inferences, likely in the form of a Gricean inference where they reasoned about possible alternative utterances a speaker could have said.

-

Object-mass nouns specify individuation lexically: Evidence from English and FrenchKhuyen N Le, Alan C Bale, and David Barner2025under review, preprint

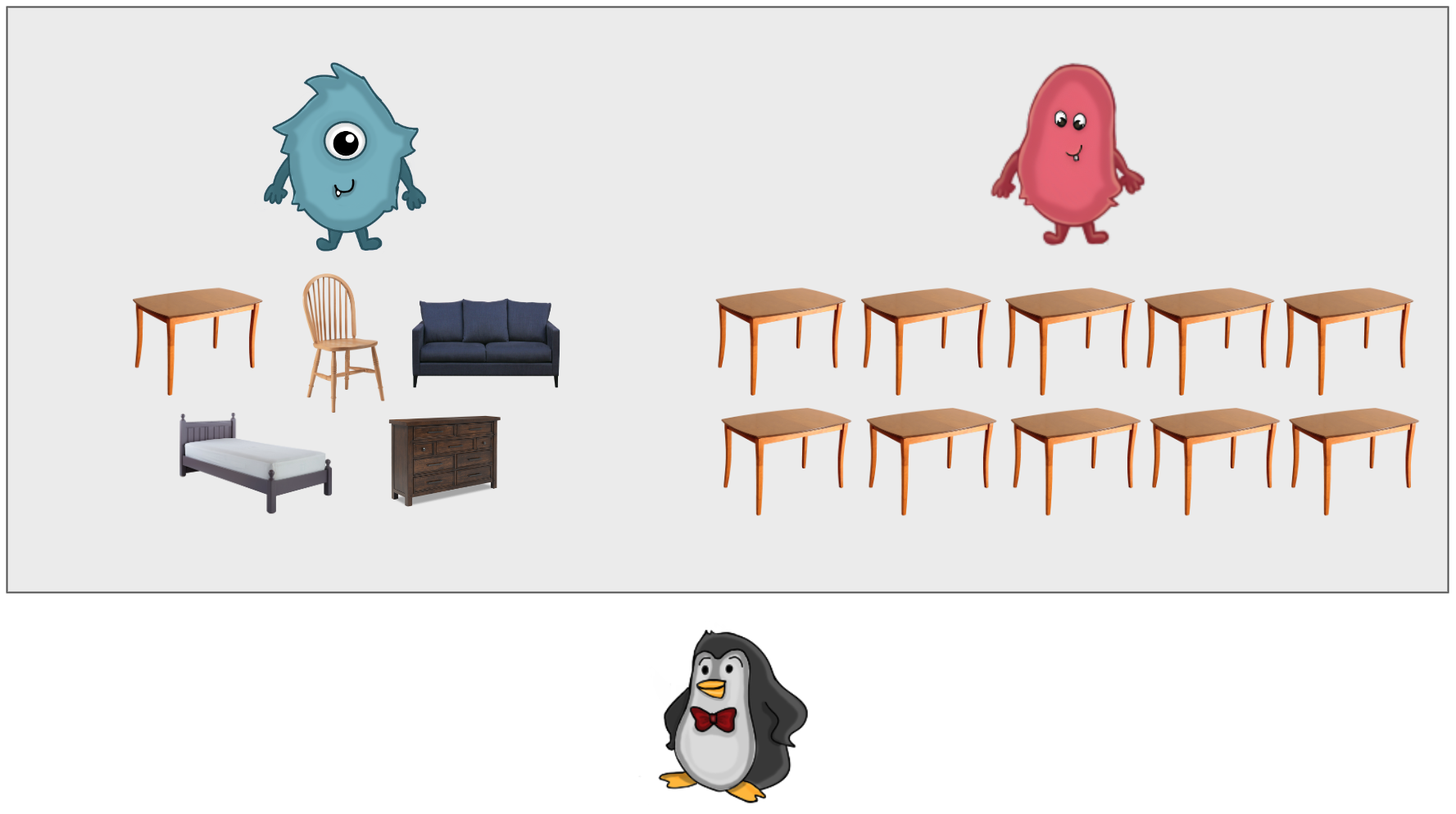

Object-mass nouns specify individuation lexically: Evidence from English and FrenchKhuyen N Le, Alan C Bale, and David Barner2025under review, preprintIn many languages, count nouns trigger a comparison by number (e.g., too many strings), while mass nouns typically do not (e.g., too much string). However, object-mass nouns like furniture exhibit mass syntax but often support a comparison by number (e.g., too much furniture → too many items; Barner & Snedeker, 2005). Some theories argue that object-mass nouns lexically specify individuation, making them semantically like count nouns in that they induce a comparison by number (Bale & Barner, 2009), while others propose that only count nouns force numerical comparisons, leaving object-mass nouns open to contextual shifts (Rothstein, 2017; McCawley, 1975). We evaluated these hypotheses by comparing English quantity judgments for object-mass nouns to (1) collective count nouns, and (2) French judgments for translations of object-mass nouns. In each case, we found that object-mass nouns behaved like count nouns, and were no more susceptible to contextual effects. These findings support the view that object-mass nouns and count nouns specify individuation to the same extent.

-

The development of cardinal extension: From counting to exact equality.Khuyen N Le, Rose M Schneider, and David BarnerDevelopmental Psychology, 2025

The development of cardinal extension: From counting to exact equality.Khuyen N Le, Rose M Schneider, and David BarnerDevelopmental Psychology, 2025Numerate adults know that when two sets are equal, they should be labeled by the same number word. We explored the development of this principle—sometimes called “cardinal extension”—and how it relates to children’s other numerical abilities. Experiment 1 revealed that 2-to 5-year-old children who could accurately count large sets often inferred that two equal sets should be labeled with the same number word, unlike children who could not accurately count large sets. However, not all counters made this inference, suggesting that learning to construct and label large sets may be a necessary but not sufficient step in learning how numbers represent exact quantities. Experiment 2 found that children who extended labels to equal sets were not actually sensitive to exact equality and that they often assigned two sets the same label when they were approximately equal, but differed by just one item (violating one-to-one correspondence). These results suggest a gradual, stagelike, process in which children learn to accurately count, learn to extend labels to perceptually similar sets, and then eventually restrict cardinal extension to sets that are exactly equal.

2023

Journal Articles

-

Syntax-Semantics Mappings of Superordinate Nouns: Mass-Count Syntax and Inferences about Functional ContextKhuyen N Le and David Barner2023preprint

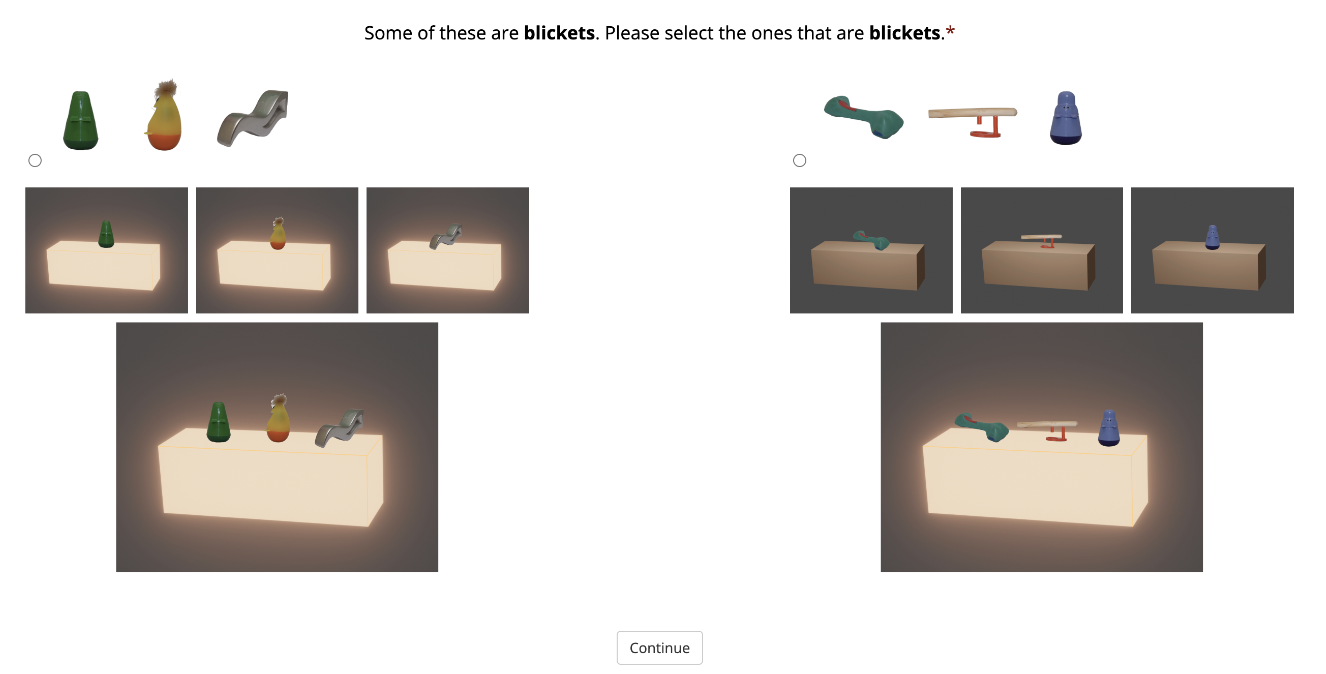

Syntax-Semantics Mappings of Superordinate Nouns: Mass-Count Syntax and Inferences about Functional ContextKhuyen N Le and David Barner2023preprintChildren’s acquisition of language has been hypothesized to be supported by a bootsimagetrapping process between syntax and semantics. Children notice the correspondence between the meaning of expressions and their lexical categories, which allow them to learn these expressions and their grammatical rules more effectively. One syntactic distinction that children in some languages have to learn is the mass-count distinction, which has been theorized to be acquired with a bootstrapping process using one-to-one bidirectional mappings between syntax and semantics. In this view, count nouns denote individuated entities, while mass nouns denote non-individuated entities (Quine, 1960; Macnamara, 1972) – a correspondence that is used by children to learn mass and count nouns. However, mass superordinate nouns that refer to individuated objects (such as furniture and jewelry) appear to be counterexamples to the bidirectional mapping theory (Gillon, 1999; Chierchia, 1998). To reconcile these counterexamples, some theorists posit that mass nouns actually denote entities that are construed to be non-individuated, regardless of their ontological status as individuated objects or unindividuated phenomena (Bloom, 1994; McCawley, 1975; Wisniewski, Imai & Casey, 1996). The current study tests a semantic contrast proposed by Wisniewski et al (1996) as corresponding to mass-count syntax for superordinate nouns: mass nouns denote objects that concurrently participate in a function, while count nouns denote objects participating in a function individually. We show that there is no evidence for the bidirectional mapping theory: adult English speakers showed no differential preference for functional context when shown either novel nouns in mass or count syntax. The results instead support a mass non-specificity theory (Gillon, 1999; Barner & Snedeker, 2006): while count nouns denote individuated objects, mass nouns are unspecified in their construal and can be flexibly individuated or not.

2021

Journal Articles

-

Is it language or is it culture? Re-examining cross-cultural similarity judgments using lexical co-occurrenceKhuyen N Le, Michael Frank, and Alex CarstensenStanford Digital Repository, 2021Undergraduate Honors Thesis.

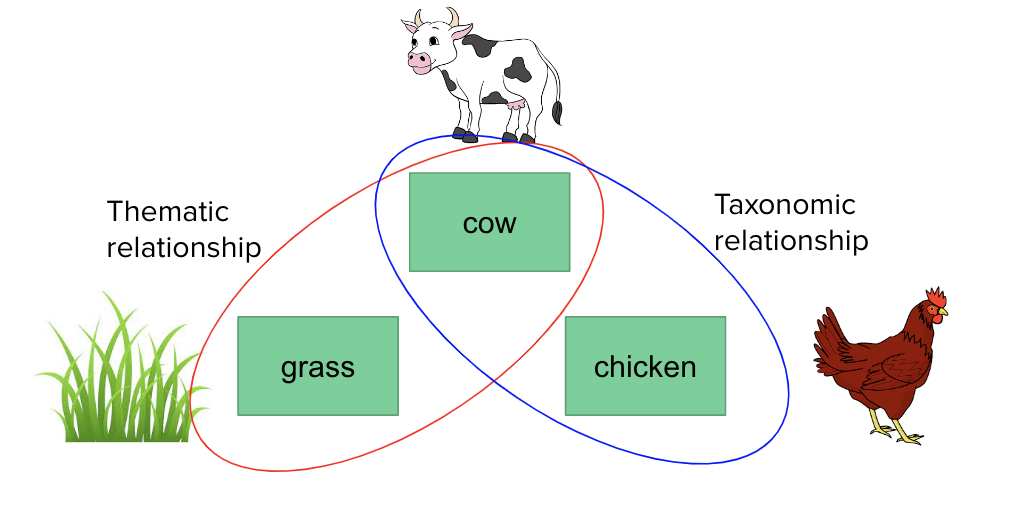

Is it language or is it culture? Re-examining cross-cultural similarity judgments using lexical co-occurrenceKhuyen N Le, Michael Frank, and Alex CarstensenStanford Digital Repository, 2021Undergraduate Honors Thesis.Is “cow” more closely related to “grass” or “chicken”? Speakers of different languages judge similarity in this context differently, but why? One possibility is that cultures co-varying with these languages induce variation in conceptualizations of similarity. Specifically, East Asian cultures may promote reasoning about thematic similarity, by which cow and grass are more related whereas Western cultures may bias similarity judgments toward taxonomic relations, like cow-chicken. This difference in notions of similarity is the consensus interpretation for cross-cultural variation in this paradigm. We consider, and provide evidence for, an alternative possibility, by which notions of similarity are equivalent across contexts, but the statistics of the environment vary. On this account, similarity judgments are guided by co-occurrence in experience, and observing or hearing about cows and grass or cows and chickens more often could induce preferences for the relevant grouping and account for apparent differences in notions of similarity across contexts.

-

Children’s interpretation of ambiguous pronouns based on prior discourseManuel Bohn, Khuyen Le, Benjamin Peloquin, and 2 more authorsDevelopmental Science, 2021

Children’s interpretation of ambiguous pronouns based on prior discourseManuel Bohn, Khuyen Le, Benjamin Peloquin, and 2 more authorsDevelopmental Science, 2021In conversation, individual utterances are almost always ambiguous, with this ambiguity resolved by context and discourse history (common ground). One important cue for disambiguation is the topic under discussion with a particular partner (e.g., “want to pick?” means something different in a conversation with a bluegrass musician vs. with a book club partner). Here, we investigated 2- to 5-year-old American English-speaking children’s (N = 131) reliance on conversational topics with specific partners to interpret ambiguous or novel words. In a tablet-based game, children heard a speaker consistently refer to objects from a category without mentioning the category itself. In Study 1, 3- and 4-year-olds interpreted the ambiguous pronoun “it” as referring to another member of the same category. In Study 2, only 4-year-olds interpreted the pronoun as referring to the implied category when talking to the same speaker but not when talking to a new speaker. Thus, children’s conception of what constitutes common ground in discourse develops substantially between ages 2 and 5.